By Minval

MOSCOW, July 17 — After more than four years of full-scale war in Ukraine, Russian academics and policy experts are beginning to acknowledge a sensitive topic long left unspoken: the war is fueling a rise in violent crime within Russia itself.

A recent study titled “The Impact of the Special Military Operation on Crime in Russia” by Willy Maslov, a researcher at the Ural Law Institute of the Russian Interior Ministry, outlines how post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), social reintegration struggles, and the breakdown of families are contributing to growing instability. Citing BBC sources, the study warns that these effects are already surfacing and are likely to intensify in the coming years.

Maslov, hardly a member of the liberal opposition or a “foreign agent,” bluntly identifies one of the key drivers of this trend: the mass mobilization and pardon of former convicts in exchange for military service. While these individuals now serve under “conditional early release,” earlier policies allowed them full pardons after just six months on the front. Many of these ex-prisoners have since reoffended, contributing to what Maslov describes as a high rate of recidivism among war returnees.

Independent experts echo these concerns, adding that the war has normalized violence across Russian society. Courts routinely take military service into account as a mitigating factor in criminal cases, and a growing number of offenses are dismissed or downplayed if the accused can demonstrate participation in the war effort. Meanwhile, PTSD remains unaddressed at scale, with aggression and instability among veterans going untreated.

While hard statistics on post-war crime in Russia remain scarce—official data is either classified or not collected—experts warn that this absence of transparency only deepens the problem. “We may not have numbers,” one criminologist told BBC Russia, “but we see the consequences in our courtrooms, in our hospitals, and on our streets.”

And yet, there is one factor that even the bolder Russian analysts tend to avoid: the nature of the war itself.

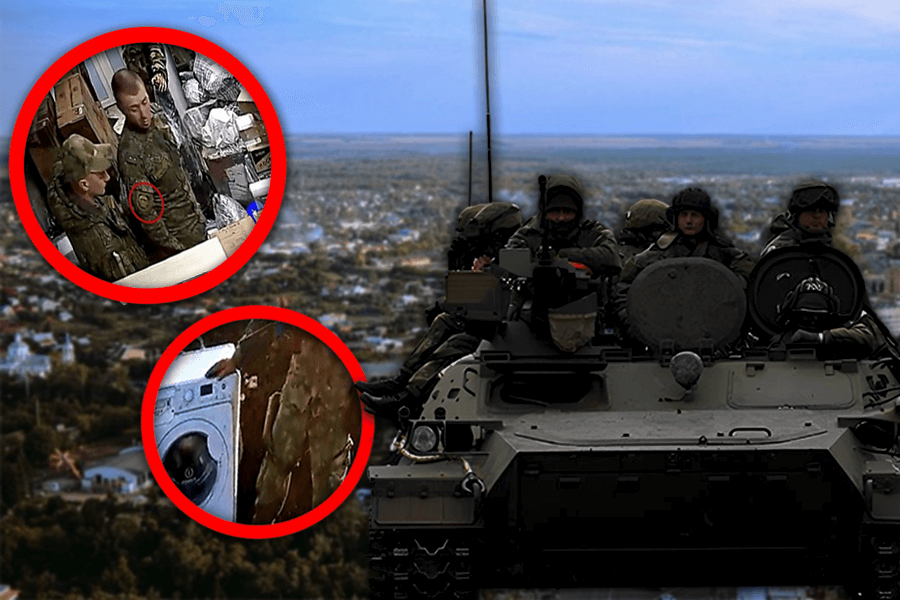

This is not merely a conventional conflict. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was unprovoked—a war of aggression against a sovereign neighbor that committed no crime other than choosing a government not aligned with Moscow’s preferences. From its outset, the war has been marred by atrocities against civilians, widespread looting, and a collapse of military ethics. The massacre in Bucha became a global symbol of Russian brutality—but it was far from an isolated incident. Footage of Russian soldiers shipping stolen washing machines and carpets back home via Belarusian post offices flooded social media. Even homemaker forums reportedly hosted discussions on how to remove bloodstains from looted bed linens.

In truth, none of this should have come as a surprise. Russian troops carried out similar abuses in Georgia in 2008—recall the iconic footage of a soldier with a golden fork sticking out of his uniform pocket. In the 1990s, during conflicts in Azerbaijan, Moldova, and Georgia, Russian forces officially “weren’t there,” yet their involvement in ethnic cleansing and looting was well documented. The infamous 366th Motor Rifle Regiment, responsible for the Khojaly massacre in Azerbaijan, was disbanded—but elite units like the Pskov Airborne Division, involved in the occupation of Lachin, were not only spared reprimand but celebrated for their “combat experience.”

The Chechen wars reinforced this trend. Ethnic cleansing was never officially acknowledged, but reports of violence against civilians and organized looting were widespread. That culture of impunity, born in the 1990s, has carried over to Ukraine, where the worst practices of those earlier wars have returned on a larger scale.

Now, men who have looted homes, terrorized civilians, and killed with impunity are returning to Russian cities. They know how little laws matter when backed by a Kalashnikov. And that knowledge—unspoken, internalized—could reshape the very fabric of Russian civil life.

Official narratives in Moscow are unlikely to admit this. As has been the pattern, authorities may try to blame rising crime on “outsiders,” particularly migrants, rather than examine the internal fallout of their own war. But the consequences of this war—on Russia’s moral code, on public safety, and on social cohesion—will not be so easily deflected.

The guns may fall silent at some point. But the violence they taught will echo long after.