By Ilgar Velizade

Last week, Iran and China took a significant step on the Eurasian transport map by signing an agreement to electrify a 1,000‑kilometer section of railway connecting the country’s western and eastern borders — from Turkey to Turkmenistan. The Razī–Serakhs line upgrade is more than routine modernization: it’s a strategic overhaul of one of Iran’s key overland arteries, with the potential to reshape freight flows between East and West.

According to Iran’s Tasnim news agency, citing Fars, the deal was reached in Beijing during a meeting between Iranian Railways head Jabarali Zakery and China Railway chairman Guo Zuchu. RailFreight reports that the project covers almost half of Iran’s main rail axis linking the Mediterranean to Central Asia. Plans include full electrification and adding a second track on the busiest sections, effectively doubling capacity. For a country where only the Mashhad–Tehran line currently has two tracks, this marks a major leap — modernizing not just capital‑bound routes but also regional hubs and international freight terminals.

The timing is no coincidence. In the first half of 2025, containerized freight between China and Iran surged by a record 260%, driven largely by high‑value industrial goods. This strengthens the China–Iran–Turkey overland route as a potentially competitive alternative to established trans‑Eurasian corridors.

The TITR Factor

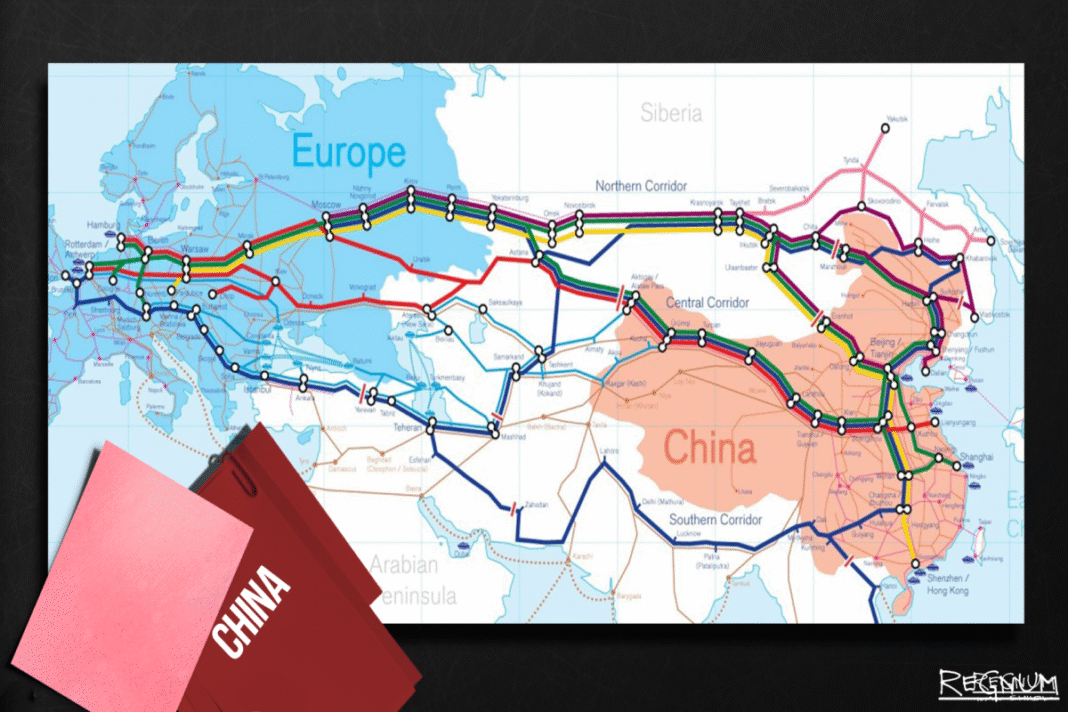

But this development cannot be viewed in isolation. The Trans‑Caspian International Transport Route (TITR), also known as the Middle Corridor, has been steadily cementing its role as a priority link between China and Europe. Its main advantage lies in political neutrality and freedom from the heavy sanctions that constrain Iran. Unlike the Iran route, TITR offers international logistics operators, insurers, and investors a path with no secondary sanctions risk or reputational penalties.

The TITR also enjoys strong backing from the European Union, which sees it as a strategic alternative to Russian and Iranian routes. Brussels is investing in Central Asian rail upgrades, streamlined customs procedures, digital cargo tracking, and green infrastructure. Multimodal flexibility — including sea legs across the ports of Aktau and Baku — allows cargo to be rerouted in case of seasonal Caspian disruptions or security threats.

Iran’s Route: High Ambition, High Risk

By contrast, Iran’s overland route faces clear challenges. Sanctions severely limit its pool of international partners, while regional instability adds unpredictability. In June 2025, for example, Israel’s airstrikes in Iran forced the cancellation of a planned China–Armenia multimodal service through Iranian territory — a reminder that even well‑prepared projects can be derailed overnight.

Two Competing Architectures

What is emerging is a dual transport architecture: one built around the EU‑backed TITR, integrated into Central Asian and European networks; the other rooted in China–Iran cooperation under the Belt and Road Initiative, geared toward SCO countries. The contest will hinge not only on economics and distance but also on each route’s resilience to geopolitical shocks and sanctions pressure.

For Iran, electrifying the Razī–Serakhs line is a bid to claim a seat at the top table of global logistics. For global shippers, however, predictability and institutional backing still tip the scales toward the TITR. In the near term, the Middle Corridor remains the more viable East–West artery — but it now faces a credible Iran–China rival, one that could evolve into a full‑fledged alternative if it can overcome the region’s political turbulence.